I have recently added a new PDF of a CBT model of OCD to the self help resources at Thrive Wellness. In this post I would like to provide some detail on this model.

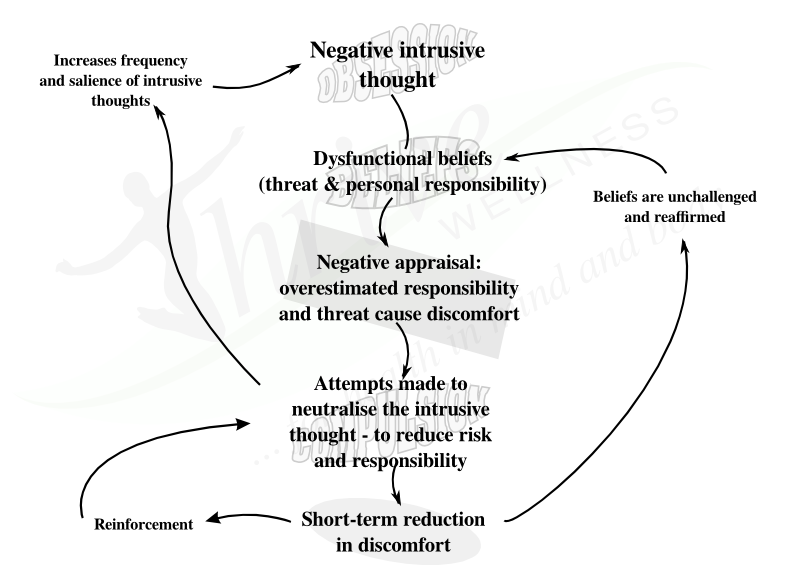

The cycle of OCD all begins with intrusive thoughts: distressing thoughts that seem to pop out of nowhere and are inconsistent with personal values. Pretty much everyone experiences intrusive thoughts from time to time. In OCD, however, these intrusive thoughts become so repetitve and distressing that they are referred to by a different name: obsessions.

When a person experiences an intrusive thought an appraisal is made. For most people, the thought is seen as so grossly inconsistent with their own values that it is shrugged off as meaningless. For some, however, there is an exaggerated sense that the thought is indicative of a significant threat and that there is a personal responsibility to ensure that perceived threat does not eventuate. This causes discomfort. Because the threat seems real and significant, action of some sort is taken to neutralise the associated risk. In OCD this is the function of compulsions: to eliminate a perceived threat.

Unfortunately, while these neutralising actions lead to some immediate relief from the distress caused by the intrusive thought, the long-term effect is essentially the opposite. By taking action to eliminate a threat that was overestimated to begin with, the underlying beliefs that caused the intrusive thought to be interpreted as threatening are reinforced. The action that was taken to neutralise the threat is also reinforced, meaning this cycle is likely to be repeated. Finally, taking action to eliminate the threat has the additional effect of increasing vigilance to the possibility of this threat occurring in future – so it is now more likely that the intrusive thought (now becoming an obsession) is going to come to mind again … and again … and again …

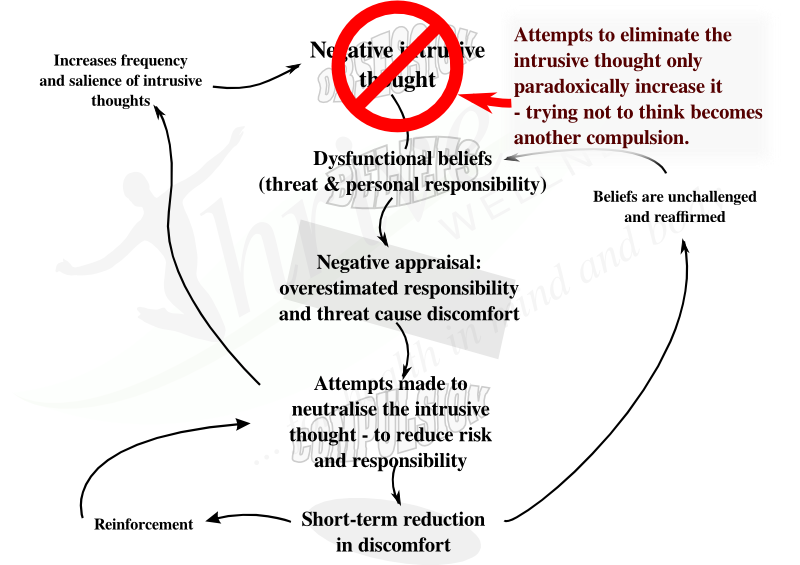

There is a paradox that occurs when a “common-sense” approach is taken to managing this cycle. Many individuals who are plagued by obsessions and compulsions, and some well-meaning counselors who do not adequately understand the OCD cycle, focus attention on trying to address the first step in the cycle. It makes logical sense: eliminate the obsessions/intrusive thoughts and the cycle breaks down. The problem is this is impossible in practice:

It is inevitable that the more you try not to think about a thing, the more you will. Don’t believe me? Try it: For the next two minutes, don’t have any thoughts about watermelons. Be honest: If any thought or image related to watermelons comes to mind, make a mark on a piece of paper to count it. Try some different strategies to eliminate watermelons from your mind: Imagine a big red “STOP” sign whenever you think of a watermelon. Recite something to yourself. Replace the thought of a watermelon with a thought of a beautiful lake.

It doesn’t work because in order to make sure you don’t think of something your mind sets up a checking procedure: you think about not thinking about watermelons and, consequently, watermelons keep popping into mind.

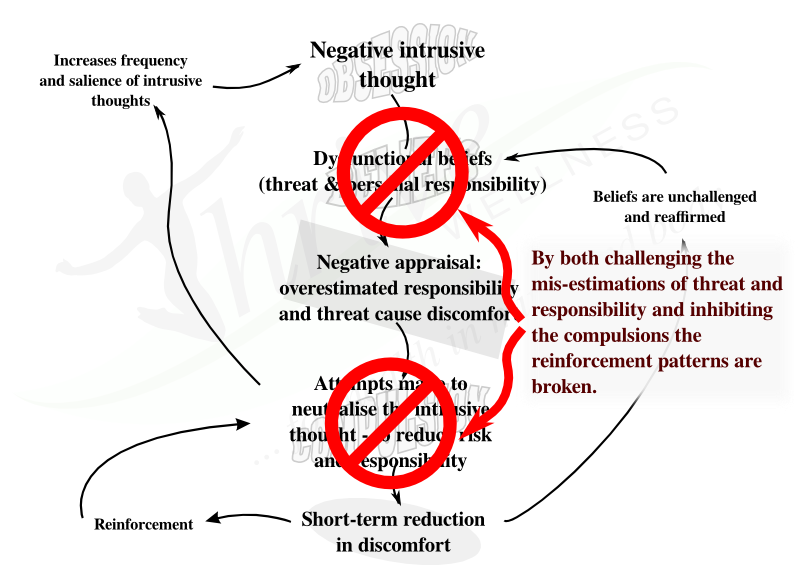

A cognitive behavioural therapy program for OCD will instead target two different points in the above model – one cognitive, one behavioural:

Here we come to one of the biggest challenges of therapy: By not addressing the source obsessions, but instead inhibiting the compulsive action and trying to challenge the overestimations of threat and responsibility, there is little relief to be had from the distress caused by the obsessions. Consequently, in the initial phases of therapy the level of distress is likely to increase. However, over time experience proves and reinforces that the triggering obsessions do not represent a real threat – because nothing bad happens despite stopping the compulsions. This, in turn, allows the obsessions to become less frequent over time.

In order for such a therapy to be possible without creating more distress than a client can handle, it is necessary to pace the process of resisting compulsions. A psychologist will develop with a client a record of the different obsessions and associated compulsions, grading them from least to most distressing. Therapy begins by challenging items that cause only a moderate degree of distress, working up as it becomes more manageable.

Leave a Reply